Executive Summary

This report details the significant payroll tax fraud scheme orchestrated by Matthew S. Brown of Palm Beach Gardens, Florida, through his company Elite Payroll and other controlled businesses. Between 2014 and 2022, Brown systematically defrauded the United States government of over $20 million in withheld employee taxes, ultimately causing a total tax loss exceeding $22 million. Operating a payroll services company catering to small businesses in South Florida, Brown collected the full amount of payroll taxes due from his clients but filed fraudulent tax returns with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), reporting and paying substantially lower amounts. The difference, amounting to millions annually, was diverted to fund an exceptionally lavish lifestyle, including the acquisition of a multimillion-dollar home, a private jet, a large sport yacht, and an extensive collection of luxury automobiles, notably including 27 Ferraris. Following an investigation by IRS Criminal Investigation (IRS-CI), Brown pleaded guilty to charges including willful failure to pay over employment taxes and filing a false tax return. On April 24, 2025, U.S. District Judge Aileen M. Cannon, presiding in the Southern District of Florida, sentenced Brown to 50 months in federal prison, followed by two years of supervised release. Additionally, Brown was ordered to pay $22,401,585 in restitution to the United States and a $200,000 fine. This case highlights the severe consequences of payroll tax fraud, the vulnerabilities businesses face when outsourcing payroll functions, and the extensive impact such schemes have on public funds, particularly Social Security and Medicare.

The Architect of Deception: Matthew Brown and His Enterprises

A. Profile of Matthew S. Brown

Matthew S. Brown, identified in court documents as residing in Palm Beach Gardens and Martin County, Florida, was the central figure behind the extensive payroll tax fraud scheme. He owned and operated multiple businesses within Martin County and surrounding areas. Public records confirm his role as Director and President of at least one key corporate entity involved, Matthew Brown & Associates, Incorporated, with a listed business address in Stuart, Florida. His position allowed him direct control over the financial operations and tax compliance activities of these businesses, including the handling of substantial funds entrusted to him by client companies for tax remittance.

B. Elite Payroll: Operations and Structure

One of the primary vehicles for the fraud was Elite Payroll, a payroll services company owned and operated by Brown. Elite Payroll marketed its services to small businesses located across St. Lucie, Martin, and Palm Beach Counties in South Florida. The core function of Elite Payroll, as hired by its clients, was to manage payroll processing, which critically included the collection and subsequent payment of withheld employee taxes to the IRS each quarter. These taxes encompassed federal income tax withholdings, as well as the employee’s share of Social Security and Medicare taxes (FICA taxes). Businesses rely on such services to ensure accurate and timely compliance with complex payroll tax regulations, entrusting these providers with significant financial responsibility and sensitive employee data.

C. Business Registrations and Licensing

The operation maintained a veneer of legitimacy through formal business structures and licensing. The entity behind the “Elite Payroll” brand appears to be “MATTHEW BROWN & ASSOCIATES, INCORPORATED,” a Florida Profit Corporation established in May 2000 (Document Number P00000043935, FEI/EIN 65-1002313). Florida Department of State records show this corporation remained listed as “ACTIVE” through early 2024, with Matthew S. Brown documented as the Director and President.

Furthermore, Matthew Brown & Associates Inc. held a specific state license relevant to its operations: an Employee Leasing Company license (Number EL416), operating under the Doing Business As (DBA) name “ELITE PAYROLL SOLUTIONS”. This license was initially issued on September 27, 2011. Notably, the status of this license is listed as “Voluntary Relinquishment” with an expiration date of April 30, 2024. Operating such a business in Florida requires registration with the Department of State and potentially specific licenses depending on the services offered, along with local business tax receipts.

The existence of a long-standing corporation (since 2000) and a specific state license (since 2011) provided Brown’s operation with a facade of compliance and professional standing. This apparent legitimacy likely played a crucial role in attracting and retaining small business clients who entrusted Elite Payroll with their tax obligations. The timing of the “Voluntary Relinquishment” of the Employee Leasing license, effective just before the end of April 2024 , occurred after Brown’s guilty plea in January 2025 but well before his sentencing in April 2025. This suggests a potential strategic decision to cease the licensed activity as legal consequences became unavoidable, possibly to preempt a forced revocation by state regulators. It underscores a level of calculation persisting even as the criminal case progressed.

D. Other Implicated Businesses

Crucially, official statements from the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the IRS consistently note that the fraud involved taxes withheld not only from the clients of Elite Payroll but also “from other businesses he controlled”. While these other entities are not specifically named in the available documents, their inclusion indicates that the scope of the tax evasion extended beyond the third-party payroll services offered by Elite Payroll.

This suggests a systemic pattern of fraudulent behavior across Brown’s network of businesses. The $20 million (later calculated as over $22 million) figure represents the total tax loss stemming from both Elite Payroll’s client funds and funds diverted from these other controlled entities. This implies that employees directly employed by Brown’s other ventures may also have had their withheld taxes stolen, broadening the pool of potential victims and demonstrating a more deeply ingrained practice of diverting trust fund taxes for personal enrichment across his entire business portfolio.

Unraveling the $22 Million Scheme: Anatomy of a Payroll Tax Fraud

A. The Mechanics of Deception

The method employed by Matthew Brown to perpetrate the $22 million fraud was straightforward yet devastatingly effective. Elite Payroll would accurately calculate the total payroll tax liability for its clients each pay period or quarter. This liability included federal income taxes withheld from employee wages, as well as both the employee and employer portions of Social Security and Medicare (FICA) taxes. Elite Payroll then collected the full amount of this calculated tax liability from its client businesses.

The deception occurred in the next step. Instead of remitting the collected funds to the IRS as legally required, Brown directed the filing of false quarterly federal employment tax returns (Form 941) with the IRS. These fraudulent returns deliberately and substantially underreported the actual wages paid and, consequently, the true amount of taxes owed by the clients. Elite Payroll would then pay only the falsely reported, lower tax amount to the IRS. Brown simply “pocketed the difference” between the full amount collected from clients and the minimal amount paid to the government. This process was repeated consistently over an extended period, allowing the stolen amounts to accumulate into the millions.

B. A Concrete Example

Court documents provided a specific illustration of the scheme’s operation. In one particular quarter during 2021, a client of Elite Payroll had a total payroll tax liability of approximately $219,000. Elite Payroll collected this entire $219,000 from the client, representing the funds intended for the U.S. Treasury. However, Brown then caused Elite Payroll to file a fraudulent Form 941 for that client, falsely claiming that the tax liability for the quarter was only about $32,000. Elite Payroll paid this falsified $32,000 amount to the IRS. Brown then retained the remaining approximately $190,000 that had been collected from the client but never remitted.

This single example reveals the sheer scale and audacity of the fraud on a per-client, per-quarter basis. In this instance, Brown diverted roughly 87% ($190,000 / $219,000) of the tax funds entrusted to him by just one client in a single three-month period. This was not marginal skimming but rather the wholesale theft of the vast majority of the funds. When this pattern is extrapolated across numerous small business clients and Brown’s other controlled entities, over the eight-year duration of the scheme, it becomes clear how the total discrepancy rapidly ballooned to over $20 million. It also starkly illustrates the immense financial risk businesses undertake when placing trust in third-party payroll providers without adequate oversight or verification.

C. Timeline and Accumulation

The fraudulent activity spanned a significant period, commencing in 2014 and continuing through 2022. Over these eight years, Brown consistently applied the deceptive practice of collecting full tax payments while remitting only a fraction based on falsified returns. This sustained, systematic diversion led to the accumulation of what was initially reported as “over $20,000,000” in unpaid payroll taxes.

Subsequent calculations by the IRS, likely incorporating penalties and interest accrued on the unpaid amounts, determined the total tax loss to the government to be “over $22 million”. This figure aligns closely with the final restitution amount ordered at sentencing, which was precisely $22,401,585. The difference between the principal amount of unpaid taxes (over $20 million) and the final restitution figure likely reflects the substantial penalties assessed by the IRS for failure to deposit and failure to pay employment taxes, along with accrued interest over the years the funds remained unpaid. This underscores that the financial damage caused by such fraud extends beyond the initial theft, encompassing significant additional statutory costs imposed by the tax system.

D. Legal Definition: Willful Failure to Pay Over Tax

The actions undertaken by Matthew Brown fall squarely within the definition of federal criminal tax offenses, particularly the willful failure to collect or pay over tax, codified under Title 26, U.S. Code, Section 7202. This statute makes it a felony for any person required to collect, truthfully account for, and pay over any tax imposed by the Internal Revenue Code to willfully fail in these duties.

The statute specifically targets “trust fund taxes”—those amounts withheld from employees (like income tax and the employee’s share of FICA taxes) that the employer holds in trust for the government before remittance. Brown, through Elite Payroll and his other businesses, had a clear legal duty to perform these actions. His consistent failure to pay over the collected funds, coupled with the filing of false returns, constitutes the failure element of the crime.

The critical element is “willfulness.” In the context of § 7202, willfulness means a “voluntary, intentional violation of a known legal duty”. It does not require proof of bad motive or evil intent, but rather that the responsible person was aware of their obligation and consciously chose not to fulfill it. Using available funds to pay other creditors, or, as in Brown’s case, diverting them for personal luxury expenditures while knowing taxes are due, is strong evidence of willfulness. Brown’s elaborate scheme and subsequent spending patterns clearly meet this standard. A conviction under 26 U.S.C. § 7202 carries a maximum penalty of five years in prison and substantial fines , aligning with the potential sentence Brown faced before his plea agreement. This strongly suggests § 7202 was a central charge in the government’s case against him.

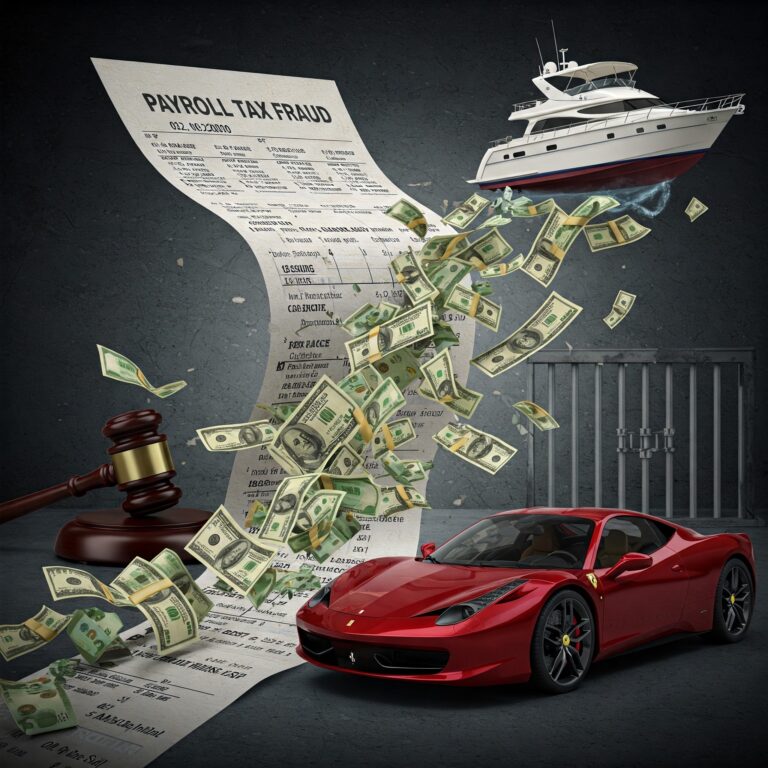

From Payroll Taxes to Porsches: A Lifestyle Funded by Fraud

A. Catalog of Luxury Assets

Instead of fulfilling his fiduciary duty to remit the withheld taxes, Matthew Brown channeled the millions of dollars diverted from Elite Payroll’s clients and his other businesses into acquiring an astonishing collection of high-value luxury assets. Court documents and official statements explicitly detail that the misappropriated funds were used to purchase:

- Commercial and residential real estate, including Brown’s own multimillion-dollar home in the Palm Beach Gardens area.

- A Valhalla 55 Sport Yacht, a large and expensive vessel known for performance and luxury.

- A Falcon 50 Aircraft, a mid-size, long-range corporate jet.

- A vast collection of luxury automobiles, specifically including Porsches, Rolls Royces, and, most notably, 27 Ferraris.

The sheer extravagance and volume of these purchases, particularly the acquisition of nearly three dozen high-end exotic cars alongside a yacht and private jet, paint a vivid picture of a lifestyle fueled entirely by the stolen tax funds. This pattern of spending served as compelling evidence for prosecutors in establishing the “willfulness” element required for the criminal charges. It demonstrated a conscious and intentional decision to prioritize personal enrichment and an opulent lifestyle over the fundamental legal obligation to pay over taxes held in trust for employees and the government. Such blatant misuse of funds likely influenced perceptions of the crime’s severity throughout the legal process.

B. Asset Forfeiture Status

While the DOJ and IRS press releases announcing Brown’s guilty plea and sentencing meticulously list the luxury assets acquired with the proceeds of the fraud , they do not explicitly state whether these specific items (the home, yacht, jet, cars) were seized by the government or ordered forfeited as part of the judgment.

However, asset forfeiture is a standard tool used by federal law enforcement in cases involving significant financial fraud. Federal law allows the government to seize assets that constitute, or are derived from, proceeds traceable to the unlawful activity. Given the $22.4 million restitution order imposed on Brown , it is highly probable that the government initiated or will pursue civil or criminal forfeiture proceedings against these high-value assets. The purpose of forfeiture in such cases is to recover the ill-gotten gains and apply them towards compensating the victim – in this instance, the U.S. Treasury (via the IRS).

The process of asset forfeiture can be complex and may involve legal actions separate from the primary criminal sentencing, which could explain its omission from the initial press releases. The substantial value represented by Brown’s multimillion-dollar home, the Valhalla yacht, the Falcon jet, and the extensive car collection makes these assets prime targets for government recovery efforts aimed at satisfying the massive restitution judgment. Therefore, while not confirmed in the provided sentencing documents, the forfeiture of these assets remains a strong possibility and a standard component of resolving fraud cases of this magnitude.

The Ripple Effect: Consequences for Businesses, Employees, and Public Funds

A. Impact on Client Businesses

The small businesses that utilized Elite Payroll’s services, despite acting in good faith by paying the full amount of their tax liabilities to Brown’s company, face potentially serious repercussions. Legally, employers bear the ultimate responsibility for ensuring that payroll taxes are properly withheld and remitted to the IRS. When a third-party payroll provider like Elite Payroll fails to make these payments, the IRS’s records will show the client businesses as delinquent on their tax obligations.

Consequently, these victim businesses could find themselves targeted by IRS collection actions, potentially facing demands for the unpaid taxes, along with penalties and interest, even though they already paid the funds to Brown. While the businesses were defrauded, resolving the situation with the IRS can be a complex, time-consuming, and costly process. They bear the burden of proving they made payments to the fraudulent provider and must navigate administrative procedures to correct their accounts, adding significant financial and operational stress on top of the initial betrayal of trust.

B. Consequences for Employees

The employees whose withheld taxes were stolen by Brown face significant risks to their long-term financial security. The unpaid taxes included crucial contributions designated for Social Security and Medicare. The Social Security Administration (SSA) tracks individual earnings and contributions over a worker’s lifetime to determine eligibility for, and the amount of, future retirement and disability benefits.

When these contributions are not remitted by the employer (or their payroll agent), the employee’s official earnings record maintained by the SSA may be incomplete or inaccurate. This can lead to lower-than-expected Social Security or Medicare benefits years down the line, potentially impacting their retirement security or access to healthcare. Furthermore, employees might encounter difficulties when filing their personal income tax returns if the withholding amounts reported on their W-2 forms (issued based on the assumption taxes were paid) do not match the (lack of) payments recorded by the IRS. Correcting these discrepancies can require substantial effort and documentation from the affected employees, demonstrating the profound human cost of payroll tax fraud that extends far beyond the direct loss to the government.

C. Damage to Public Funds and Trust

The timely payment of payroll taxes is fundamental to the functioning of the U.S. government. As highlighted in the official announcements, these taxes are the primary source of funding for the Social Security and Medicare systems, upon which millions of Americans rely. Additionally, withheld federal income taxes constitute a major portion of the nation’s overall revenue stream.

Brown’s diversion of over $22 million directly deprived these essential programs and the U.S. Treasury of critical funds over an eight-year period. Beyond the monetary loss, large-scale fraud schemes like this erode public confidence in the fairness and integrity of the tax system. They create the perception that compliance is optional for the wealthy or well-connected, potentially discouraging voluntary compliance among honest taxpayers. The IRS and DOJ emphasize the importance of prosecuting such cases not only to recover funds but also to maintain public trust and deter future violations.

D. Employer and Third-Party Payroll Provider Liability (TFRP Context)

The Internal Revenue Code includes a powerful provision designed specifically to address the failure to remit trust fund taxes: the Trust Fund Recovery Penalty (TFRP), codified in IRC § 6672. This penalty allows the IRS to hold individuals personally liable for the full amount of unpaid trust fund taxes (withheld income tax and the employee’s share of FICA taxes).

To be held liable for the TFRP, an individual must meet two criteria: they must be a “responsible person,” and they must have acted “willfully” in failing to collect, account for, or pay over the taxes. A “responsible person” is broadly defined and can include corporate officers, directors, partners, employees with significant financial control, and even third-party entities like Payroll Service Providers (PSPs) or individuals within them who exercise control over funds. “Willfulness,” as previously discussed, involves a conscious, voluntary disregard of the duty to pay the taxes.

The TFRP is a civil penalty equal to 100% of the unpaid trust fund tax. Crucially, it allows the IRS to pursue the personal assets of the responsible individual(s), bypassing the corporate structure. This ensures personal accountability even if the business entity itself is defunct or bankrupt. Matthew Brown’s actions clearly positioned him as a responsible person who acted willfully, making him personally liable for the TFRP on top of his criminal culpability. The $22.4 million restitution order reflects this personal liability for the unpaid trust fund taxes, penalties, and interest. The TFRP serves as a potent deterrent, emphasizing the high degree of legal responsibility associated with handling employee tax withholdings.

Bringing Brown to Justice: Investigation and Prosecution

A. Investigation by IRS Criminal Investigation (IRS-CI)

The investigation that ultimately led to Matthew Brown’s conviction and sentencing was conducted by IRS Criminal Investigation (IRS-CI). IRS-CI is the dedicated law enforcement arm of the IRS, possessing unique expertise in unraveling complex financial crimes and exclusive jurisdiction over criminal violations of the Internal Revenue Code. Their involvement signifies that Brown’s actions were assessed early on as potentially rising beyond civil non-compliance to the level of deliberate, criminal tax evasion and fraud.

IRS-CI special agents employ sophisticated investigative techniques, including tracing money flows through bank records, analyzing financial statements, conducting interviews, executing search warrants, and potentially leveraging data from Bank Secrecy Act filings like Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) and Currency Transaction Reports (CTRs), although the use of BSA data was not explicitly mentioned in the Brown case materials. IRS-CI investigations are known for their thoroughness, focusing on building robust, evidence-based cases suitable for prosecution. The agency consistently maintains a high federal conviction rate, often exceeding 90% in adjudicated cases, reflecting the strength of the investigations they refer for prosecution. Facing an investigation by IRS-CI, with its specialized financial acumen and track record, likely presented Brown with overwhelming evidence of his guilt, making a guilty plea a more pragmatic outcome than risking a trial.

B. Prosecution Team

The prosecution of Matthew Brown was a collaborative effort between the Department of Justice’s Tax Division and the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of Florida (USAO-SDFL). This partnership is common in significant tax crime cases, combining the specialized expertise of the Tax Division attorneys with the local knowledge and trial experience of the USAO.

Several attorneys were specifically named in connection with the case. Trial Attorney Andrew Ascencio of the Tax Division and Assistant U.S. Attorney (AUSA) Michael Porter for the Southern District of Florida handled the prosecution at the sentencing phase. Earlier, at the guilty plea stage, the prosecution team included Trial Attorneys Andrew Ascencio and Ashley Stein, both from the Tax Division, along with AUSA Michael Porter. Additionally, former AUSA Diana Acosta was credited with assisting in the investigation phase. The involvement of multiple attorneys from both the national Tax Division and the local USAO underscores the resources dedicated to prosecuting large-scale financial fraud.

C. Key Officials Announcing Actions

The public announcements regarding major developments in the case were made by senior officials within the DOJ and the USAO-SDFL. The final sentencing announcement was made jointly by Acting Deputy Assistant Attorney General Karen E. Kelly of the Justice Department’s Tax Division and U.S. Attorney Hayden O’Bryne for the Southern District of Florida. Karen E. Kelly holds a senior leadership position within the Tax Division, overseeing enforcement efforts. Hayden O’Bryne was appointed U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Florida effective January 28, 2025. He is an alumnus of the University of Miami and previously served as an AUSA in Miami and worked as an associate attorney at K&L Gates.

Notably, the earlier announcement regarding Brown’s guilty plea was made by different officials: Acting Deputy Assistant Attorney General Stuart M. Goldberg of the Tax Division and then-U.S. Attorney Markenzy Lapointe for the Southern District of Florida. The change in leadership, particularly the appointment of U.S. Attorney O’Bryne between the plea and sentencing , highlights the continuity of prosecution efforts within the Department of Justice. Cases proceed based on institutional priorities and the merits of the investigation, regardless of routine personnel changes at the highest levels of the Tax Division or the U.S. Attorney’s Office.

D. Court Proceedings (Southern District of Florida)

The case against Matthew Brown was adjudicated in the United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida, specifically within the Ft. Pierce Division. The official case docket number is 2:24-cr-14045.

Key milestones in the court proceedings include:

- September 27, 2024: The government filed an “Information” against Matthew S. Brown, charging him with two counts. An Information is often used instead of a Grand Jury indictment when a defendant has agreed to plead guilty.

- January 2025: Brown formally entered his guilty plea. Magistrate Judge Shaniek Mills Maynard issued a Report and Recommendation regarding the change of plea on January 13, 2025.

- January 28, 2025: U.S. District Judge Aileen M. Cannon adopted the Magistrate Judge’s report and formally accepted Brown’s guilty plea.

- April 24, 2025: Judge Cannon imposed the sentence on Matthew Brown.

The timeline from the filing of the Information in late September 2024 to the sentencing in late April 2025 spans approximately seven months. For a complex financial fraud case involving over $22 million, this represents a relatively swift resolution. This compressed timeframe strongly suggests that a plea agreement was negotiated between Brown’s defense and the prosecution prior to the formal charges being filed, streamlining the judicial process and avoiding a lengthy and resource-intensive trial preparation phase.

The Sentence: Accountability and Context

A. Details of the Sentence

On April 24, 2025, U.S. District Judge Aileen M. Cannon delivered the sentence for Matthew Brown’s extensive payroll tax fraud scheme. The sentence comprised multiple components aimed at punishment, deterrence, and restitution:

- Imprisonment: 50 months (four years and two months) in federal prison.

- Supervised Release: A term of two years of supervised release to follow the completion of his prison sentence. Supervised release involves monitoring and specific conditions imposed by the court.

- Restitution: An order to pay $22,401,585 in restitution to the United States (specifically, the IRS). This amount represents the total calculated tax loss, including principal, penalties, and interest.

- Fine: A separate monetary fine of $200,000 payable to the United States.

B. Presiding Judge: Aileen M. Cannon

The judge presiding over the case and responsible for imposing the sentence was U.S. District Judge Aileen M. Cannon. Judge Cannon was appointed to the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Florida in 2020 by then-President Donald Trump. Born in Colombia and raised in Miami, she is a graduate of Duke University and the University of Michigan Law School (magna cum laude). Prior to her judicial appointment, Judge Cannon worked in private practice at the law firm Gibson Dunn and served as an Assistant U.S. Attorney in the Southern District of Florida from 2013 to 2020, handling major crimes and appellate work. She has been a member of the Federalist Society since law school.

While Judge Cannon has presided over other high-profile and politically sensitive cases that have drawn significant public attention , her role in the Brown case involved the standard duties of a federal judge in a criminal matter. This includes accepting guilty pleas, considering arguments from both the prosecution and defense regarding sentencing factors (including the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines), and ultimately imposing a sentence deemed appropriate under the law. Her background as a former federal prosecutor in the same district provides direct experience with federal criminal statutes and sentencing procedures relevant to cases like Brown’s. The sentence imposed appears to fall within the expected range for a fraud of this magnitude resolved via a guilty plea, indicating a conventional application of the judicial process in this instance.

C. Comparative Sentencing Analysis

Evaluating the severity of Matthew Brown’s 50-month prison sentence requires context. Federal sentencing is complex, guided by the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines but ultimately determined by the judge considering various factors: the calculated financial loss, the nature of the offense, the defendant’s criminal history, acceptance of responsibility (often through a guilty plea), any cooperation provided, and the need for just punishment and deterrence. Payroll tax fraud sentences can vary significantly based on these case-specific elements.

The following table provides a comparison of Brown’s sentence with outcomes in other recent, large-scale payroll tax or related fraud cases, based on available DOJ press releases:

| Defendant Name | Case Location / Year | Approx. Tax Loss / Fraud Amount | Prison Sentence | Key Notes | Source(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matthew Brown | SDFL / 2025 | $22.4 Million (Payroll Tax) | 50 Months | Guilty plea, Luxury assets (yacht, jet, cars) | |

| Joseph Schwartz | DNJ / 2025 | $38 Million (Payroll Tax) | 36 Months | Guilty plea, Nursing home empire | |

| Andrew Park | DOJ Ref / 2025 | $14+ Million (Payroll Tax) | 30 Months | Guilty plea, Software CEO | |

| Owner (Walczak) | DOJ Ref / 2025 | $4.4 Million (Payroll Tax) | 18 Months | Guilty plea, Healthcare co., Yacht purchase | |

| Brent Brown | MDFL / Plea 2025 | $3.8 Million (Payroll Tax) | Pending | Guilty plea, Latitude 360 CEO | |

| Hialeah Tax Preparer | SDFL / 2025 | $20 Million (Return Prep Fraud) | “Almost…” | Guilty plea, Tax prep business | |

| Sandy Gonzalez | WDTX / 2024 | ~$300k (Return Prep Fraud) | 24 Months | Guilty plea, Tax prep business |

Note: Sentencing details can vary based on specific charges and guideline calculations.

This comparison reveals considerable variability in sentences even for multi-million dollar payroll tax fraud schemes resolved through guilty pleas. For instance, Joseph Schwartz, responsible for a significantly larger tax loss ($38M vs. $22.4M), received a shorter sentence (36 months vs. 50 months). Conversely, Andrew Park, with a lower tax loss ($14M+), received a notably shorter sentence (30 months).

This disparity underscores that the total dollar amount of the fraud, while a primary factor in the Sentencing Guidelines, is not the sole determinant of the prison term. Other elements play crucial roles. Aggravating factors, such as the extreme and ostentatious use of fraud proceeds for personal luxury (as seen with Brown’s yacht, jet, and 27 Ferraris), can signal a greater level of culpability or disrespect for the law, potentially leading to a sentence higher in the guideline range. Mitigating factors might include substantial cooperation with investigators or unique personal circumstances. The specific charges to which a defendant pleads guilty and how the loss amount is calculated under the complex guideline rules also heavily influence the outcome. Therefore, while Brown’s 50-month sentence is substantial, it is not necessarily inconsistent with outcomes in similar cases when considering the likely aggravating impact of his lavish spending funded by the eight-year fraud.

Conclusion: Lessons from the Elite Payroll Collapse

The case of Matthew Brown and Elite Payroll serves as a stark reminder of the significant damage wrought by payroll tax fraud and the severe consequences awaiting those who perpetrate such schemes. Over eight years, Brown executed a calculated deception, betraying the trust of his small business clients and misappropriating over $22 million in funds designated for vital government programs like Social Security and Medicare. This systematic theft not only resulted in substantial financial loss to the U.S. Treasury but also potentially jeopardized the future benefits of employees whose contributions were stolen and created significant legal and financial burdens for the victim businesses.

Brown’s eventual sentence—50 months in prison, over $22 million in restitution, and a hefty fine—underscores the seriousness with which the federal justice system views the willful failure to remit trust fund taxes. The investigation by IRS-CI and the prosecution by the DOJ Tax Division and the USAO-SDFL highlight the government’s commitment to identifying and holding accountable individuals who exploit their positions for personal enrichment at the expense of the tax system. The application of personal liability, likely through the Trust Fund Recovery Penalty mechanism, ensures that perpetrators cannot simply hide behind failed corporate entities.

For businesses, particularly small enterprises relying on third-party providers, the Elite Payroll collapse highlights the critical importance of due diligence and ongoing oversight when outsourcing payroll functions. Verifying that tax deposits are actually being made, reconciling payroll records, and understanding the provider’s licensing and reputation are essential safeguards. The facade of legitimacy maintained by Brown through corporate registrations and state licensing demonstrates that surface appearances can be deceiving. Ultimately, the case reinforces the fundamental importance of payroll tax compliance as a cornerstone of fiscal responsibility and underscores the significant legal and ethical obligations associated with handling employee withholdings. Sources used in the report